Grease in pipes is not dirt. It is fuel.

Feb 3, 2026

5 min

Editorial note: This article was originally published by Alkion service s.r.o., a valued member of EVHA.

As the topic is highly relevant to current discussions in ventilation hygiene and indoor air quality, we are pleased to share an English translation with the wider EVHA community.

Fuel accumulates in kitchen pipes over the years. Not symbolically, but literally. Grease that does not drain away does not disappear and does not ventilate itself. When it ignites, it becomes a fire accelerant and, if the ventilation system is not maintained, an open path for fire to spread throughout the building. If kitchen exhaust systems are not regularly inspected and cleaned, it is no longer a matter of comfort or hygiene. It is a risk just waiting for the right moment.

When you cook, grease is produced. And that ends up in the ductwork.

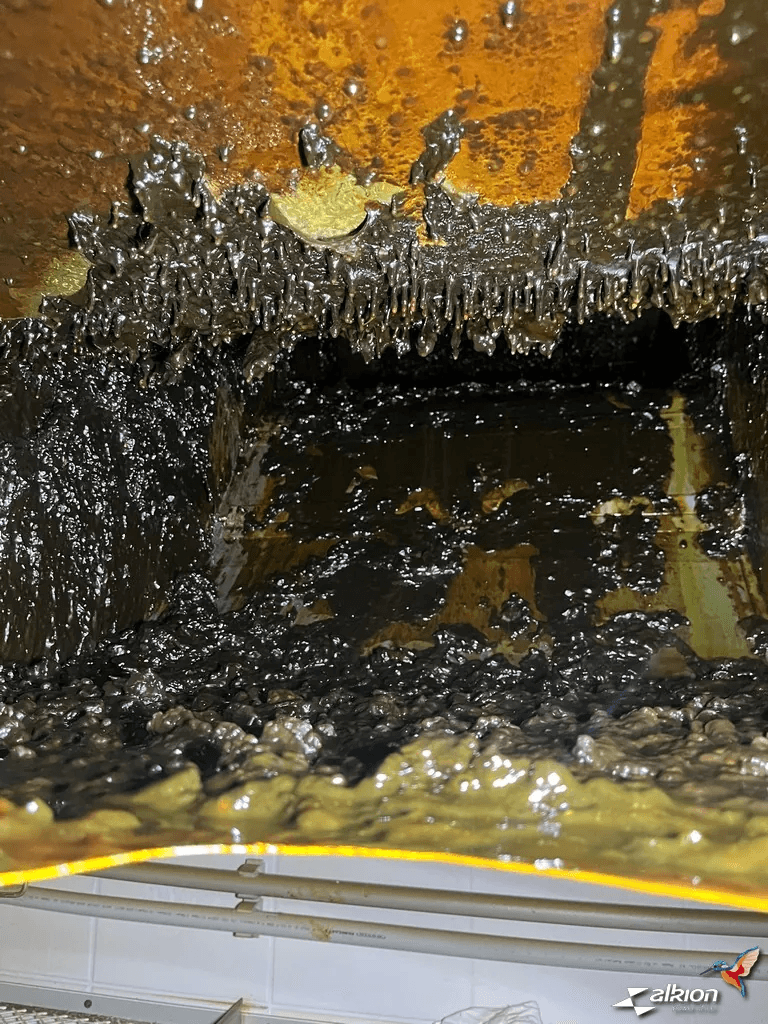

Professional kitchens produce large amounts of grease aerosols. Warm, small particles are carried along with steam by the air flow into the hoods and further into the exhaust ducts. Some of them are captured by filters, but a significant portion gradually settles and condenses on the walls of the ducts. If the system is not cleaned regularly, a continuous layer of grease forms.

This layer is not passive. It does not simply age away. It thickens, hardens, binds other impurities, and most importantly, it is flammable. In a closed duct that runs through the entire building, it becomes ready-made fuel.

Fire does not seek a path. The ductwork offers it one.

A fire in a restaurant usually does not start in the ductwork. It starts on the cooking equipment—in a pan, on a grill, in a deep fryer. The difference between a local fire and a fire that spreads through the building lies in what is above the kitchen.

Once flames or extremely hot gases enter the hood, the grease in the ducts acts as a continuous combustible path. Fire can spread very quickly outside the kitchen area, above suspended ceilings, into risers, and between fire compartments. This is no longer a hypothetical scenario, but a repeatedly confirmed reality from practice.

A fire damper that does not close is just a piece of sheet metal

Projects assume that fire dampers will stop the spread of fire. However, their function is conditional on one essential thing: they must be able to close.

In clogged kitchen exhausts, grease does not only settle on the walls of the ducts. It also sticks to the mechanical parts of the dampers – axles, bearings, seating surfaces. A damper that is supposed to react in a matter of seconds is stuck. At a critical moment, it closes only partially, or not at all. Without regular cleaning, an active safety feature becomes a non-functional detail that can no longer be relied upon.

When the ductwork doesn't work, neither does the kitchen

The fire risk is the most serious, but it is far from the only one. Clogged ductwork means higher pressure losses and poorer draft. The result is a kitchen full of odors, moisture, and heat. Air returns to the space instead of being effectively removed.

Cooks work in an environment where it is difficult to breathe, they tire quickly, and their performance declines. Odors can also spread to the back of the house or guest areas. The system is running, the fans are humming, but it is failing functionally.

What practice and numbers say

The new European standard EN 15780:2025 is based on the principle that the cleanliness of ventilation systems must be a controllable and maintained condition, not a random action. Kitchen exhaust systems are among the most heavily used installations, and the recommended intervals reflect this:

check the condition of ducts and hoods at least once every 6-12 months,

in intensively used kitchens (all-day operation, frying, grilling) every 3-4 months,

filters, grease traps, and functional elements, including fire dampers, must be checked more often than the ducts themselves.

The standard also works with measurable pollution limits. For existing systems, 200 micrometers (0.2 mm) on the inner surface of the ductwork is considered the acceptable limit. In kitchen exhaust systems, this value is often exceeded many times over in practice. This is not fine dust, but compact layers of grease several millimeters thick (and centimeters of buildup are not uncommon).

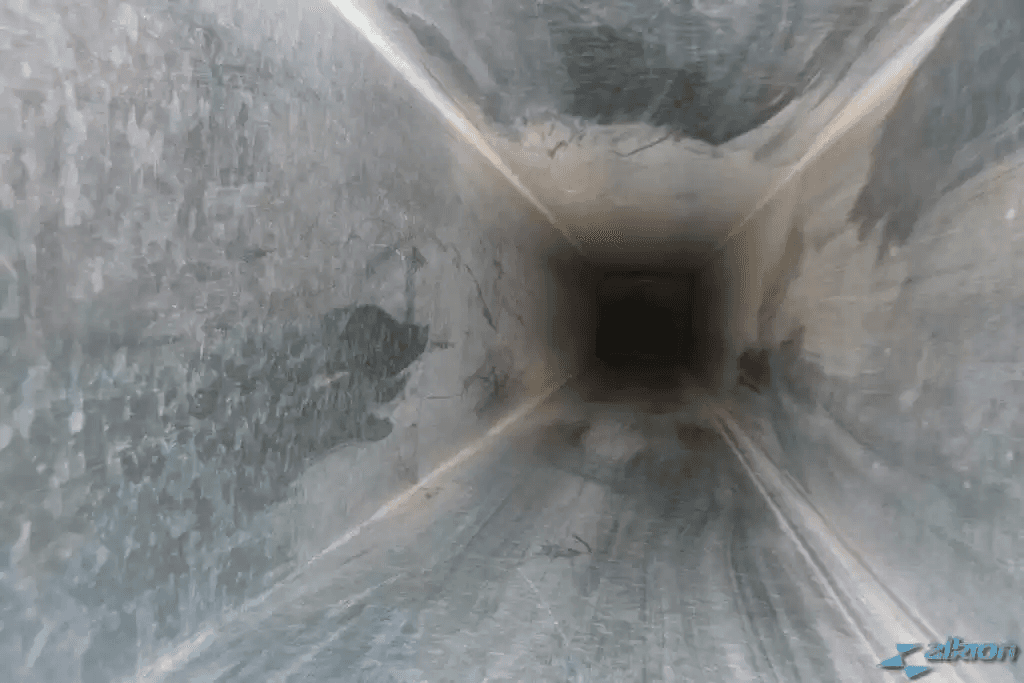

The ideal condition is not a luxury. It is a basic requirement.

The ideal kitchen ventilation system is not one that you admire. It is one that you are unaware of. The ducts are clean, dry, and free of continuous deposits. Fire dampers move freely and respond immediately. The exhaust actually removes the air, and the kitchen remains a workspace, not a risk zone.

Restaurants don't burn down because they cook in them. They burn down because the system that can't be seen is overlooked for a long time. And kitchen ventilation is exactly the system that needs to be addressed before you smell smoke.

EVHA perspective

Grease contamination in kitchen extract systems is not only a hygiene issue – it is a serious fire risk that requires professional assessment, regular inspection and properly trained specialists.

At EVHA, we support high standards, certified training and knowledge sharing across Europe to help reduce these risks and improve safety in commercial kitchens and ventilation systems.

🔗 Learn more about Kitchen Extract Hygiene Training & Certification

[ contact us ]

Got a question?

Want to join?

Contact us.

Are you interested in becoming a member or simply have questions about European Ventilation Hygiene Association?We’d love to hear from you, so don’t hesitate to contact us today.We’re here to assist you with your inquiries.

© Copyright Notice EVHA 2025

EVHA